BY ALESSANDRO RIVA (2010)Images of myth reverie water

In 1988, the journal Nature published an article that caused a sensation. This article, signed by the French immunologist Jacques Benveniste, supported a very eculiar and extremely meaningful theory – which would later give rise to deep divergences, accusations, counter-accusations and denials in the international scientific community. This theory became known as the discovery of “water memory”.

Water molecules, according to Benveniste, possessed some “memory” of the antibodies they had come into contact with. As if all the water on earth – the water of the rivers, the lakes, the sea, the one flowing from mountain springs as well as from our kitchen taps – were aware of what it had seen or “felt” on its way, and retained a faint memory of the things it had come into contact with. As if water had a memory, thus, in a wider sense, maybe also a conscience, a thought – in brief, an unconscious. Gaston Bachelard is the philosopher who best meditated upon the deep meaning of dreaming, of daydreaming, or rather of that peculiar process which can be hardly translated and that in French is called rêverie (maybe it might be called dreamy daydream; this has much to do with poetic imagination and also with letting oneself go to poetic creation, contemplation and memory – when “a little bit of night matter” remains “forgotten in the clarity of the day”; and enables poets, dreamers and artists to get rid of the function of reality, in order to enter a sychic state when even the real world “is absorbed by the world of imagination”, and in which “memories are fixed in overview pictures, scenarios prevail over drama, sad memories fade away into melancholy”); Gaston Bachelor, indeed, wrote many important pages about the imaginative and poetic power inside water images, and the very matter of water. Memory, water and poetic imagination are, according to Bachelard, three closely connected terms.

“There is a water sleeping at the bottom of each memory”, the philosopher writes in The oetics of Reverie, following the same path as those oets who, by and in their works, bear witness to “an aspiration to go beyond the limit, to go upstream, to recover the vast lake with still waters where time rests” – that lake is always in us “as the place where a motionless childhood still resides”. The water Bachelard talks about in his metaphor is still, calm (an eau dormante), because it is deep, deeper than the very nature of our real memory – a water prior to the being, or “below the being and above the nothingness” – that searches for not only our real recollections, our real childhood, the one we really lived, but also a melting pot of possible childhoods, of imagined lives – plausible if not real -, and of “recollections going beyond our memory, of dreams which have never disappeared”.

“Childhood”, the philosopher writes, “is a human water, a water which comes out of the shadows”; and this childhood “of mists and flashes”, this life “experienced in the slowness of limbos”, “grants depth to the birth”, or rather to thousands of possible births, because – by our own ability to daydream, or by the work of artists who are able to start these psychic mechanisms inside us -, we give birth to thousands of other possible lives besides the one we really lived: “We originated so many beings!”, Bachelard writes. “So many lost springs went on flowing! The rêverie of our past, the rêverie in search of childhood, seems to give space to lives which have not been lived, but just imagined. […] In the rêverie we get in contact with possibilities which destiny was not able to take advantage of. A big paradox emerges from our childhood rêveries: this dead past has a future in us, the future of its living images, the future of rêveries that is opening up in front of each recovered image”.

Since remote ancient times, the image of water – just like the image of flight – has carried out the function of archetype of man’s deep conscience, as well as of its own origin. Countless water images originated some of the most ancient myths in the history of mankind. Ancient Greeks considered the Ocean as the origin of the Gods and all the creatures, even the Genesis describes the Spirit of God “hovering over the waters” when the earth was still “formless and empty, and darkness covered the deep waters”. In the Vedas, the sacred texts of Hinduism, instead, we can read “an expanse of water with no light” being the prime cause of everything. On the other hand, the amniotic fluid water is where every human form of life originates – it is our origin and the “zero point” of our conscience. There is an extraordinary ancient Hindu myth in which the fluid, magic, irrational reality of water is extremely meaningful and symbolic: a myth in which reality is defined as the origin of the magical consequence of a water dream, where the real and the dreamed intersect until you cannot distinguish one from another anymore: and the unifying element is, once again, just water.

This myth is named after the figure of saint Mârkandeya, and his journey in the infinite waters of god Vishnu’s body: Mârkandeya sees the body of the god asleep in the middle of a vast expanse of water – a deep, black, primordial water -, and he mistakes him for a mountain range; he approaches him, then the god swallows him, spits him out, and swallows him again. The sight of primordial waters is in itself, according to saint Mârkandeya, a sign of confusion: he does not know if the waters, and himself along with them, were the work of a dream – the dream of the god who dreams the world, the waters from which the world originated, and us, who are integral parts of the world. Water is therefore the symbol of a birth – the birth of the world, and, along with it, of ourselves – as well as the image of a loss: the loss of the conscience of the world – the real world, as we are used to knowing it – in favour of a truer and deeper revelation: the cosmos and human nature. In the vast and deep waters of the unconscious lays the risk of losing your own earthly nature, to somehow rejoin the depth of the cosmos, and thus the secret and truer core of your own spiritual nature.

Annalù has lived all her life with her feet immersed in water and a good head on her shoulders – just like Cecilia Scacerni, the main character of the Italian literature masterpiece by Riccardo Bacchelli, the Mill by the river o (unfortunately not enough appreciated and studied). Annalù’s destiny, though, was not to be born along the river Po, that crosses and gives name to one of the most flourishing Italian plain – the Po valley – but along the river Piave, whose name recalls many stories, battles, adventures, disillusions and hopes (as well as suffering and deaths) that make up not only our history but also what is called our “identity” – in this case, national identity. Annalù lives along the Piave, in a ile-house. In the past, it was made of wood, today it is built of bricks. A house, as she tells us, that “breathes” because of all the stories that have passed over the river and have been lived, “and has the same salty smell of the water. A water,” Annalù says, “that is green-blue and because we are near the sea, sometimes ‘runs upstream’ (it has the power to reverse) and is salty, sometimes it ‘runs downstream’ and is sweet”.

Annalù does not live in any house: she lives in a house that once belonged to her father, and before that, to her grandmother.

Her grandmother’s name was Anna but she went by the name of “Nanea”. She was a “boatwoman” and her job was to ferry whoever passed that way from one side of the river to the other. Annalù has lived through the stories she heard and collected in the family, thousands of river stories. She has listened to them, she has re-told them, she has re-lived them, literally. In retrospect, she has been part of them, she has been leased and excited by them and has suffered, recording those songs, those passages, those isolated images, stuck to the retina through old black and white photos found in a drawer. Photos of kids who cross the river, balancing on an old boat, a happy and carefree youth from another era; or a guy taking a girl in his arms and laughing, laughing, laughing, happy in his youth, a youth lasting a moment, and then disappearing; young days of the past, on the river, memories of other times, other clothes, other hairdos, other atmospheres, certainly: yet, the same water, the same river, the same house as today, made those memories her own, and allowed the sedimentation and the digging of a small place inside her, a remote and inaccessible place, made of that impalpable and airy substance of dreams and ancestral memories – lived or imagined memories, since even memories experienced by others, at times, can become our own, and dig a safe and boundless place in the deep water of our unconscious.

Here are some of her grandmother’s memories, belonging to the Piave “…many foreigners fell into the water… most of them were drunk. Carrying their bodies ashore was such a hard work, I don’t know how I managed! At the end I got used to it, but the first years, at night, I kept thinking about them and I could not sleep. I thought: how could I have handled all this? If it only were for one year, two, three… it would have been easier. But I have lived buried for thirty years!” Thirty years along the river. The boatwoman. Water. Whirlpools. Streams. Floods. And the river tricks…. The deep, twirling, endless water of the river….

“In the fifties the Piave shores were like a beach… until Luigi drowned. Before that, from noon to three, four in the afternoon there were forty, fifty people going there. Moreover, every family had its access to the shore for their animals. It was always so crowded – so joyful. That eriod was a happy time. After the accident, since the very following day, no one came anymore. Death had traumatized everyone.”

Today we don’t know who Luigi was. Nevertheless, sometimes, other people’s memories get stuck to our hearts and start digging. Death came and took a man’s life, Luigi’s, who died one day, thirty years ago, in the iave. It ruined the party for someone. Youth, perhaps, ended the same day for many others. The river showed its dark, terrible side. A sudden death. And a piece of memory, impalpable and light, passes from one mind to the other, from one generation to the next one: but, relentless, it sticks to the folds of time. It gets into our dreams. Today. More than fifty years later. What are dreams made of? What “dreamy” matter are they made of? And why the restless water, that runs, boils, beats, that at the bottom seems so dark, almost black, why does that water seem to be part of us, of our dreams, of our story, of our soul?

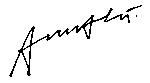

Annalù went back to her river. She went back to water. She started one of those revealing paths, in which the impalpable matter of dreams, memories, multiple sensations, family and intimate history tries to reckon with reality. Mixing with it. Trying to win over it. To keep it upon thorns, in suspense, in equilibrium. Annalù plays on a delicate thread. It can break easily. It can become rhetorical. It risks to disappear as a drop in a river. But Annalù does not get discouraged. She picks up objects from the river, just like her grandmother picked up drowned bodies. She fishes for relicts. Old bloated barks. The river garbage. The damned. The souls, the remains of a thousand tales touched by the river. The ancestral memory of water. And she resuscitates them.

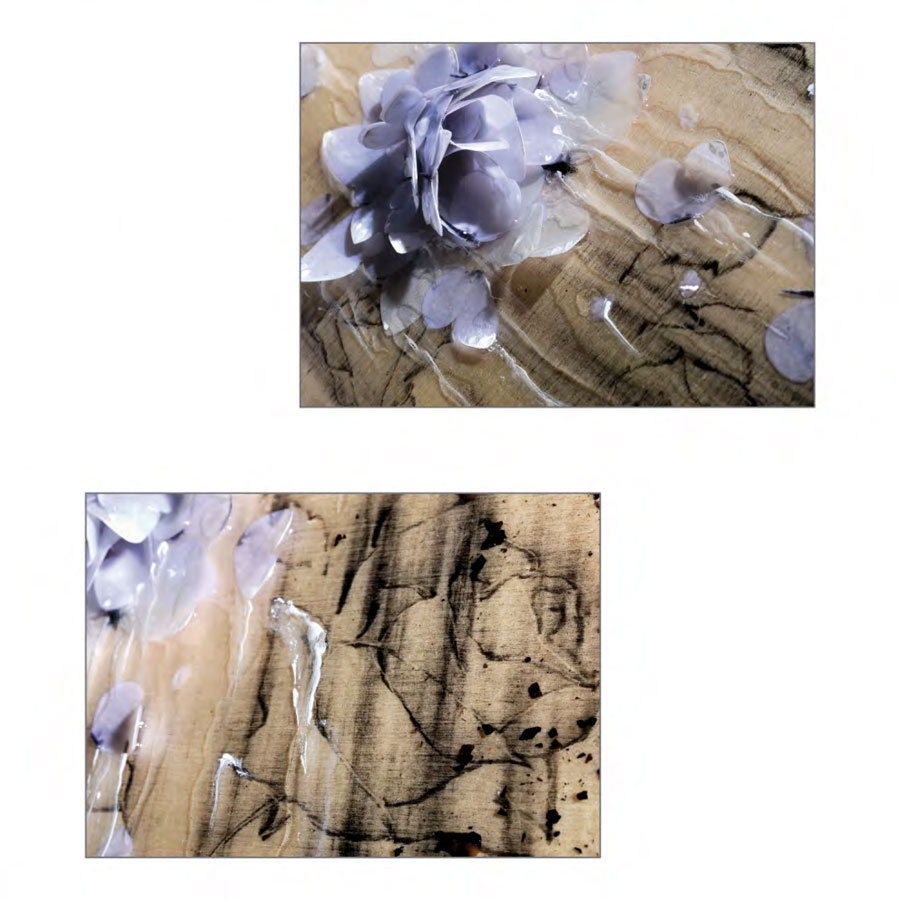

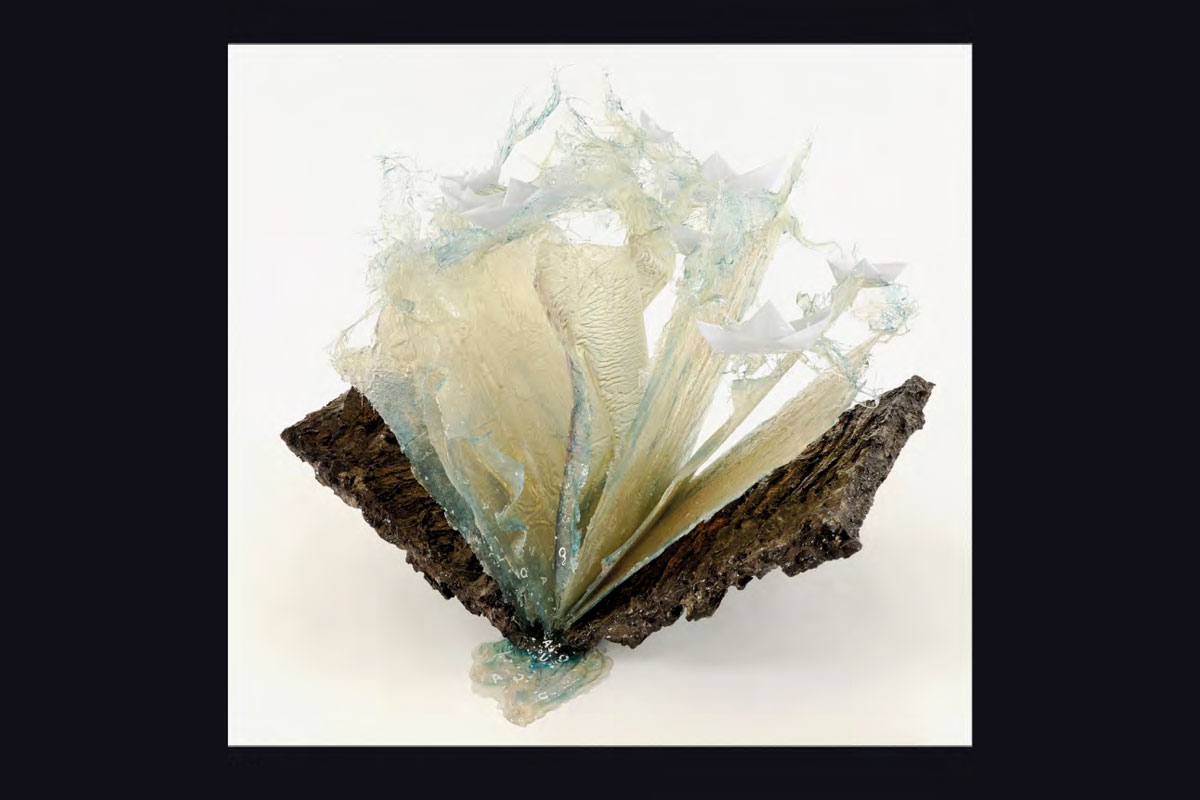

She brings them back to life. She leaves them there to sediment, through the rough matter of memory and time. Then, she manipulates them. She moulds them. She makes them immortal, before the corrosion and decay of time could sink them into oblivion. “The paths, the “harvest”, the tales contained in the material – the artist says – fascinated me from the beginning” Annalù assembles strange, sometimes even incongruous materials, that seem unwilling to be bond together. Material oxymoron. Resins. Barks. Fiberglass. Strange encounters. Bizarre shapes. Imaginary architectures. Metamorphoses.

Alchemies of a never static, fluid matter. A matter always in motion, fluid and inorganic. Swerving to the left. Telling stories that only well trained ears, eager to listen to the liquid, immaterial sound of dreams, can erceive. Rêveries. Dreams of childhood, of old tales, of stories never lived. Water, wood, fiberglass (the material used to build boats), resin – fluid materials which, manipulated by the artist, evoke ancient, ancestral stories. Old legends, that seem drawn on water. Exactly – books made of water. Could a more evident oxymoron possibly exist in the world? Usually books are made of paper. Paper is wood, a solid, static matter. An earthly matter. Annalù turns solids into fluids, material into immaterial, stable into unstable. The boundary is thin, the rope is always tight to the limit. At the end, how can the image of water be stopped still?

In Annalù’s sculptures, water drops are stopped in the very moment they are being sprayed to the sky. Annalù is following the impossible dream to stop the instant, right when it is happening. She fights against time and expects to win. To do so, she uses the metaphor of the Water element – symbolizing both the passing of time and its birth. Before water, there was no world. There was no man.

Time did not exist. Resin drops stretch out crazily and rashly: they are frozen instants, in a time which does not seem human any longer. How can time be stopped still through form? “I believe this, too, is a part of my work: I think the magic of an object can also be felt in its ventured shapes. Water is such an unpredictable element… which I had to manage, manage as an alchemist… as an artist”. Alchemy, indeed; a dive into one’s unconscious, into one’s ancestral memory. Manipulation of matter, of reality.

In his essay “Kabbalah and Alchemy”, Arturo Schwarzwrites “the term alchemy indicates a preliminary or rimeval stage of chemistry.

However, alchemy has never been a proto-science as, although sharing science’s purpose – conquering knowledge – its aim was achieving self-consciousness and the unification of the divided self. Right from its dawning, alchemy has had a transcendental dimension, an ethical connotation and a mystical approach… the term defining the alchemic work, the hilosopher’s stone, clarifies that the alchemist’s quest aimed to the highest knowledge (aurea apprehensio). Research has a fundamental importance in the alchemical writings, because it is only through research that the alchemist can obtain the knowledge he aspires to. Thus, the quest was more important than the prize, or better still, the quest was the prize, since knowledge, self-consciousness, implies freedom which is, as already explained above, the purpose of alchemy”. It is no coincidence that Jung was extremely interested in this aspect of alchemy, pointing out the strong similarities between the metals transmutation and the alchemist’s contemporary psychic transformation, highlighting the importance of the alchemist’s learning process and sychological, inner reformation (what Jung defined the “individuation” process), which indeed the search for the “highest knowledge” entailed.

“I talk about a world frozen in metamorphosis” the artist says, “and alchemy is lightness”. To stop time. To catch the shape of dreams. To conquer one’s memory and, through it, the very ancestral memory of the world. Annalù’s crazy wager proceeds cautiously and resolutely at the same time. Jellyfish of the unconscious. Magical puddles. Hanging trees. Unreal sleeping beings. Impossible chairs. Floating benches. Swings of plumes. Impalpable butterflies. “They are all works containing both myth and reality, an earthly optical vision and a dreamy one” says Annalù. The springs of the inner myth are still flowing out, free, unrestrained. “How many beings have we originated! How many lost sources have kept on flowing! In the rêverie”, wrote Bachelard, “we get in touch with possibilities that destiny has not been able to exploit”. The paradox of rêverie, in Annalù’s works, is more intact than ever. As crystal clear, as quivering as the river water. “This dead past has a future in us, a future made out of its living images, a future of reveries opening before every recovered image”.

Text of the catalog “Images of water, myth and Reverie” by A. Riva. Personal Exhibition, Wannabee Gallery, Milan, 2010.