by ALESSANDRA REDAELLI (2022)Onirica

When faced with Annalù’s works, one first experiences a sensation of synaesthesia. What one perceives as matter captures the gaze very much like pouring rain – a soft sound that is also absolute and inevitable. A breaking of waves in front of the tsunami rising at the centre of her Dreamcatchers, or an intense rustle, like a murmuring of fairies, as we fix our gaze on the restless foliage of her windswept trees. This rustle intensifies the moment we realize that those leaves are wings, and that in an instant everything is going to take flight.

In an artistic panorama that is immense yet somehow encrusted, set in its accustomed ways, an artist who knows how to create something completely new is a very rare find. Because if it is true that resin has long been legitimized as a fit material for art, the way in which Annalù uses it, at the intersection between nature and artifice, between the great tradition of Venetian glass blowing and the furthermost frontiers of technology, has a completely new taste and produces unique results. Foremost among these is the estranging visual impact of her art, due not only to the synaesthetic sensation mentioned above, but also to an immediate awareness that the freshness of gesture, the impression of lightness, of an object that seems to exist almost as a natural phenomenon, is the outcome of long and meticulous labour, of a battle with matter, of a complex act of thinking and planning.

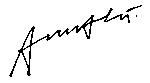

Annalù’s meeting with resin has the character of fatality. Ever since her artistic debut, her research has focused on lightness and the ineffable, but above all on the translucency of water. Water is, in fact, this artist’s alchemic element. Her roots are close to Venice, a city steeped in moving, restless, elusive water. Also, water has been the determining factor in her family life for two generations, starting with a grandmother who used to ferry passengers from one shore of the river Piave to the other, at Passarella. The artist herself has chosen to live on a house built on piles, as if water were an element without which she cannot afford to live, like a contemporary siren who needs, every now and then, to grow back her scaly tail.

It is resin, therefore, that teaches her to do something that would have seemed impossible before: sculpting water. It is resin she loves and fights, her passion and her torment, a precious element which has to be faced with a mask and double gloves, because its splendour conceals a dangerous soul, like a wild animal that the artist has got to tame. In the course of several years Annalù has managed to tame the beast, learning its secrets and exploiting its infinite qualities, inventing a system to endow it with the transparency of diamonds and a seducing serpentine fluency, pouring it down drop by drop into an alien appearance – a liquid appearance – and arming it to make it rock-solid.

On the multi-faceted notes of resin, Annalù composes the mysterious symphony that is the substance of her work – a symphony whose score is always, inevitably, based on a perfect balancing act between two opposites, on the fascination of the oxymoron. It is the paradox of a powerful, assertive lightness, that gives no quarter and imposes itself on the gaze; of artificial nature, alive in the detail of veins, of sap, of blood, yet so perfect that it is unthinkable in this world; of a tangible reality and the impossibility of its existence as shown to the viewer; of a liquid solidity which keeps dripping eternally, yet never exhausts itself in a real movement because it is firm in its immobility; of lace that uncoils with the perfect regularity of a fractal, and then unveils itself, free and wild as a foamy wave.

The space in which we move is that of a reality that is entirely other, like when we dive deep into a dream and realize that certain scenes – which had seemed logical at first – are kept together by a plot whose sense is now lost to us. But the quest itself is intriguing: we are looking forward to opening the next door, and we feel sure that it will present us with an explanation before we wake up.

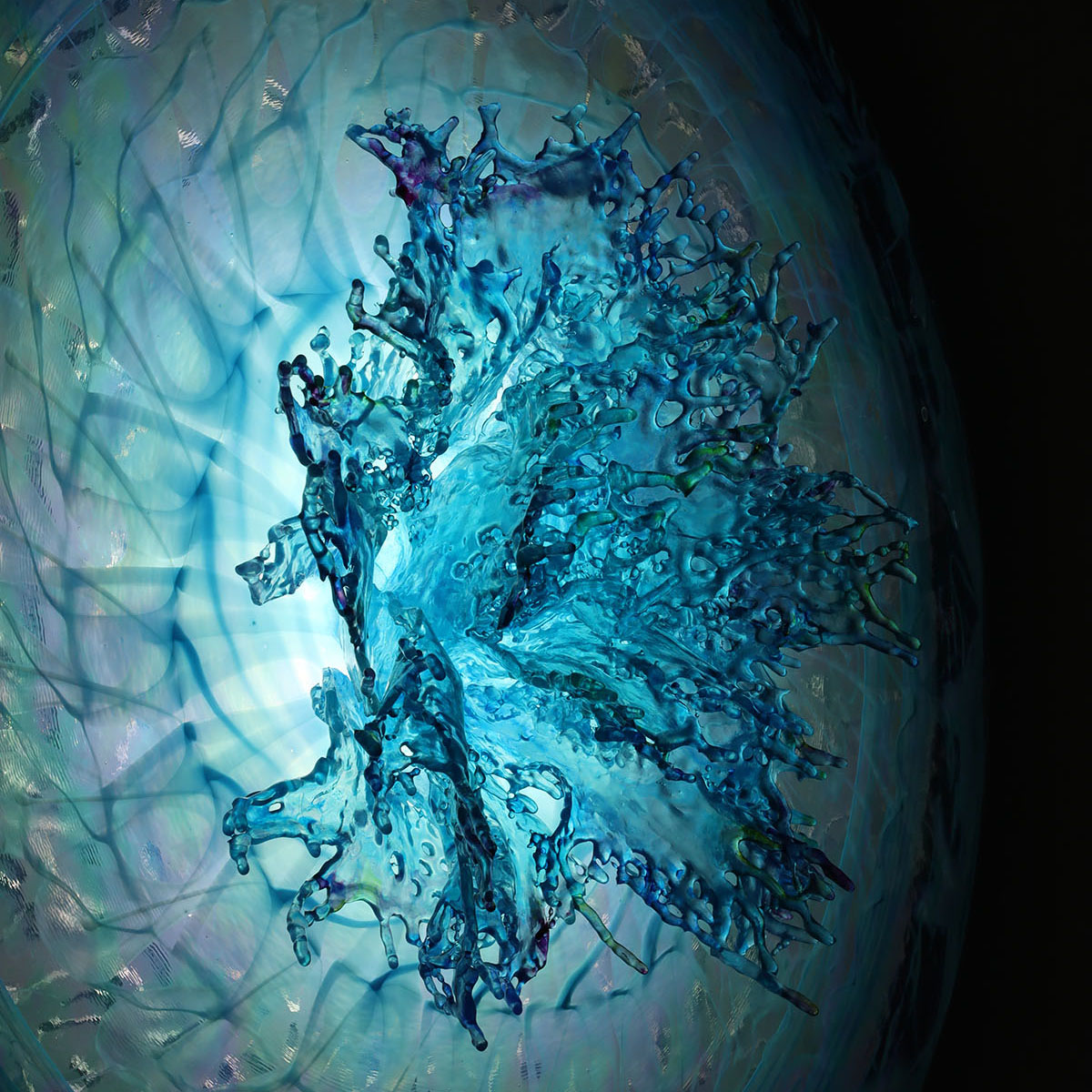

And just as in dreams, there are powerful symbols here. They are scattered in details which we read only gradually, enchanted as we are by the near-neobaroque splendour of a sumptuous surface, and then driven to explore in more and more depth. Consider the butterflies that hover vibrantly around the foliage or off the Dreamcatchers. The first thing that strikes us is of course their beauty: those bright colours in the tradition of Venetian mosaic glass, made throbbing by the artist’s proficiency. In time we begin to see the butterfly in her complete meaning, and we grasp the agonizing necessity of that imminent flight, the sense of a destiny that must be fulfilled immediately: the animal is as beautiful as a flower, but also equally short-lived. And then, if we are willing to delve deeper, the butterfly also takes up its meaning of “psyche”, of soul. Suddenly the heart of that whirlpool loses its purely aesthetic connotation and reveals itself as a stargate, a passageway to another dimension. At a single stroke the object in front of us is amplified, acquires double and triple bottoms, and our feeling of hypnotic attraction finally finds an explanation.

Annalù rethinks the role of the shamanic artist in a contemporary key, but also with a highly distinctive alphabet, where beauty and aesthetic satisfaction occupy centre stage. She is an alchemist who transforms matter and hardens water under our very astonished eyes, but she is also a woman who runs with wolves – or, more appropriately, rides dolphins – and who knows how to prepare spells in which we can initially lose ourselves, only to discover later that we have become richer and more aware. It happens when she inserts golden waves in the turquoise whirlpool of her Dreamcatchers, and almost inadvertently, in our heads, we hear the sound of something that entered our consciousness in Venice: Byzantine gold, the footprint left behind by the East.

And once again, this awareness reverses the artistic experience: because if that is mystical gold, the colour blue certainly becomes the Virgin Mary’s mantle – which adds further layers to our reading. Or when she decides to have the roots of her trees (knotty roots, contorted trunks that the artist fishes out of the waters flowing just beside her home, and which she dries and rests for months before subjecting them to treatment and turning them into elements of her work) cling not to something solid, but to a transparent shape reminiscent of ice – and then we suddenly realize that their clinging is fearfully fragile, and that the foliage and truncated movements of that tree express terrifyingly human emotions.

Annalù also sets traps for us with her Sagittas, which draw inspiration from the downward arrow imprinted on the backs of so-called “forbidden books”. Transfixed by the arrow that immortalizes the instant, here the written word begins to gush like blood from a cut artery, ready to invade everything, heedless of bans and censorship, free to capture us in order to give us back to ourselves, changed forever; while this gushing of thought that invades space brings to mind the rapture of reading which sweeps us away, far from reality.

And then there is her liquid lace, which bears the stigmata of the artist’s past research (on kilim carpets and Nautilus shells, which she investigated to try and understand the mysterious mathematical rules which regulate their nature and their beauty), but is also the harbinger of new narratives combining siren legends and insubstantial bridal veils, the tradition of Burano lace and the transparency of Murano glass, the softness of fabrics and the intangible substance of sea water.

There are thousands of interlacing evocative impressions in this multifarious, mutable alphabet: and suddenly one turns away from what appears to be an oriental arras woven by a fairy, and finds oneself looking at a spiral of colours rotating like the eyes of the serpent Kaa, ready to hypnotize and devour. Lenticular prints that seem to be moving, colours changing under our very eyes, flat surfaces mysteriously turning three-dimensional: all these testify to Annalù’s entrance into a technological beyond which she was destined, sooner or later, to claim for herself.

And then, just a moment later, here are Hermes’ winged feet, this time in bronze; the right direction for their flight given, again, by the butterfly. These works originate from the Jumps in the blue realized by the artist a few years ago – where the body turned itself into purest water, the spray lifted by that final step before taking flight.

And after all, come to think of it, the greatest strength of Annalù’s work, its most precious essence, is her ability to capture the moment and to immortalize something we could call – with another oxymoron – the eternal instant. Because there is nothing more exciting than the illusion that we can stop the instant. That we can fix it in a piece of matter, and just stand there and observe it. That we can afford the luxury, in short, of existing in the perfect harmony of the present. As the zen masters teach us. Here and now. Surrounded by beauty.